First published in May 2019 in Issue 12 of The Gourmand, an award winning, biannual food and culture journal.

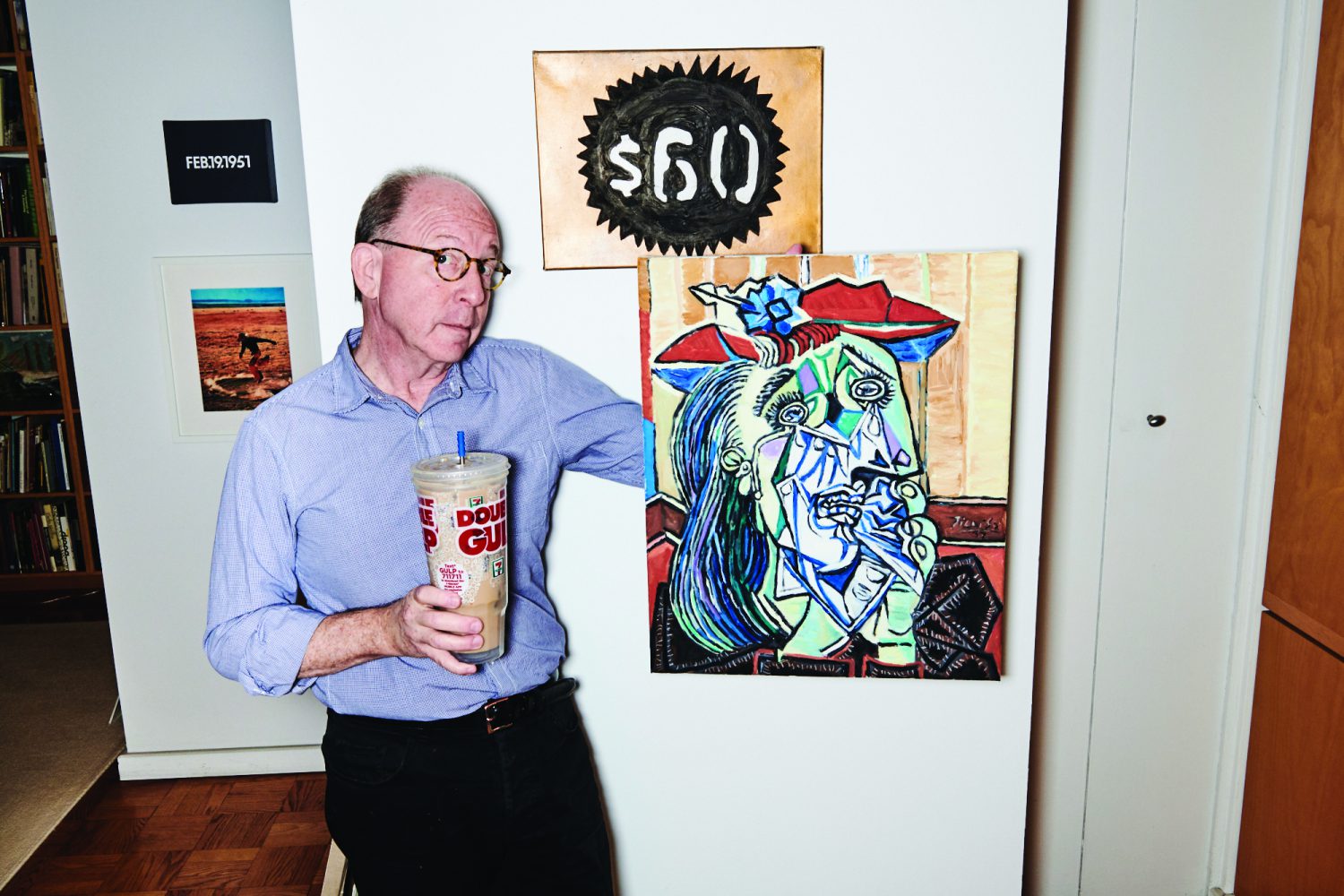

Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic Jerry Saltz, who has strong opinions on art-market groupthink, coffee and elitism. David Michon called him for a stimulating chat

Photography: Bobby Doherty

Jerry Saltz is a man of refreshing integrity and Panglossian spirit—endearingly optimistic, he’s also sarcastic to the point of sardonic, political (he’s aggressively anti-Trump), and defiantly condemnatory of the art market, art fairs and highfalutin’ auctions. But he’s an undying believer in the power of art. Jerry Saltz became an art critic at 41, after working as a long-distance truck driver and trying his hand at being an artist. Now in his late 60s, he brought home New York magazine’s first Pulitzer Prize in 2018—it’s at that magazine that he has served as senior art critic since 2006. His persona takes him far. He’s lovable but no-holds-barred; he’s forceful but self-deprecating; he’s intelligent and accessible. And he’s mastered social media: he has nearly a million followers across Twitter and Instagram. His posts have been described as ‘antics’, flip-flopping as they do between reverence and scorn for artists known and unknown, between calls to activism and strangely personal recounting of his coffee habits. Those habits are, on top of being refreshingly anti-establishment (in the context of him being a cultural tastemaker), perhaps a good metaphor for his take on art.

Is now still a good time to speak?

Perfect. Thank you for calling and calling on time. I’m grateful.

Well I’m very grateful for your time. As I mentioned, the starting point for this was how refreshing I find your coffee habits.

Thank you.

I think perhaps it says something interesting about how you view not just coffee but the world. But first, tell me about Jerry plus coffee.

Let me just say this—this is complicated—I think of myself as somebody raised by animals. I left home at a young age. No degrees, no education. I was a smart-alec smartass, who really never listened to anybody. And so there are a lot of things I don’t know how to do. I can’t spell. I can’t cook. I don’t speak any foreign languages. I barely read anything until I was much older—and one of the things I didn’t know how to do was make coffee. I could make tea.

So,

when my doctor said it’s OK to drink coffee, because I love the drug, I

thought, “Oh, well this

is easy,” and I went to our local deli on the corner, and would buy coffee, put

it in the refrigerator overnight and either reheat it, or lately my wife and I

have been on a drag of just doing huge iced coffees.

And that’s how we do it. I buy a bunch of Seven- Eleven Double Gulp cups, and we wash and reuse them and the tops and the straws—everyone yells at me for “using too much plastic, Jerry!” They’re the same cups we’ve used, you know, for a couple of years. And every morning I fill them up with ice and a little bit of milk, a little bit of coffee, a little bit of water and Sweet’n’Low or Stevia. Insert straw. Drink. That’s the ritual.

And this is a ritual that is shared by your wife Roberta? Did she also not have any kind of coffee- making capacity?

No! We’re both art critics. My wife, Roberta Smith, is the co-chief art critic for The New York Times, and our motto, in a way, is: “We are not part of this world.” We are not part of society. It’s a tunnel-life for us, to be among the last five or six weekly art critics, writing and getting paid something for it.

“And does my coffee taste worse than your coffee? Not to me it doesn’t! Taste—and this is important— taste, like art, is subjective.”

Being part of this dying breed also means that we have no time. I do nothing except see about 20 or 30 shows a week in museums, galleries, alternative spaces, etc. Then I come home, and get panicked, and think I should quit because I’ve run out of things to say. The demons visit me, and then every morning I sit down—no matter what—and begin writing, because I know if I don’t begin, I’ll never begin. Because there’s nothing worse on this earth than writing, as all writers know. And then, once I start, I’m in heaven.

You’ve just called me, and when I looked up it was 11.30 am. I’ve been here since 8.30, and I’m absolutely happy after being absolutely miserable for the first hour. And so this coffee ‘ritual’, as people call it, is really just another time-saving device for me. Other people will say it’s faster and easier to make it at home. You may be right. I’m not questioning that, but this is the bad, or good, habit I’ve found to expedite my use of coffee. And does my coffee taste worse than your coffee? Not to me it doesn’t! Taste—and this is important—taste, like art, is subjective. All art is subjective. Not everyone will like van Dyck or Turner. I’m not a Turner fan. There’s a consensus that these artists—like certain coffees—are great, but each of us picks and chooses our own, and develops a kind of language, a memory of taste.

You’ve posted on social media about your coffee habits a couple of times now. Can you tell me about the reaction?

I was horrified that everyone else in the world was horrified that this was my taste! And I was thinking, “When did the world get so fussy, and so aristocratic, or whatever you want to call it, that to drink deli coffee was somehow a sacrilege?” And I find that really wrong, and not open—and too focused on a kind of fetishisation of accepted taste. So, everyone now is drinking latte-frappé-cappuccinos with cinnamon and swirly cream. Everyone else drinks the same thing, and I don’t know where personal taste goes in that. Again, I’m not saying my coffee is better. I’m not saying my coffee is any good. Art is what works. Art is what works for you. This coffee works for me.

“I’m a cow-whisperer. Which I was taught to do up there by people that maintain these heritage cows nearby. And that’s my only hobby now —it used to be opera. But that got too expensive.”

Am I missing something by not, you know, every morning doing a, whatever—cold press? I have no idea what that is. Every morning measuring out my coffee, combining special beans, sending away for special additives… Am I missing things? Of course I am, of course I am. But, hey, I don’t have much time. This is how I’m using my time.

Do you think there’s a problem in the art world more broadly, a kind of tyranny of a particular type of taste—whatever is à la mode?

Very much. I think that we see it in the market most obviously, that the market is said to be so smart— but that’s wrong. Really all the market is, is a self- replicating organism: people in the market buy what other people in the market have already bought, and so it only reinforces it. I would say we see it in art, we see it in food, we see it in music. We see it in films, obviously. We see it almost everywhere. I’m just saying we contain multitudes, and that we can’t be horrified if you like Fragonard, the Rococo painter, more than you like, um, Rembrandt. It’s possible there are people in the world like that. I have better moments, lately, with Fragonard.

At the risk of belabouring the parallels between coffee and art, coffee, in an American context used to be exclusively Maxwell House and Folgers, or bottomless diner coffee. It was very much an ‘every person’s drink’. And now it’s been remade as some kind of elite pursuit, like wine.

In the art context, I know you point to cave drawings as the origin of contemporary art—but do we see that, several thousand years later, society unfairly sees art as something for the elite? Are you on a mission to disrupt these mass-to-elite culture shifts?

A couple of things: cooking, like art, is for anyone. It’s just not for everyone. What this means is it’s not elitist. But art is specialist. It’s something you have to delve into. It isn’t easy. It’s a mysterious, silent language. It isn’t about understanding, it’s about experience. We don’t ask “What does Mozart mean?” And yet too many people in the world, the general audience, look at art and say: “Well I don’t like it because I don’t know what it means.” Well, I’m not sure what my work means either. I don’t even know how, you know, how to do it. I just do it.

Art is not elitist—that’s yet another cynical attack. Is cooking elitist? No, it isn’t. But in certain sectors it gets more and more refined, and that then becomes fetishised, and then becomes a kind of priest craft, where you must only eat in certain ways, and at certain restaurants. And, to me, that’s just another fake religion. But, I would add, whatever gets you through the night. Whatever gets you through the day, the speaking to demons. I’m fine with that. Even if it means drinking deli coffee out of gigantic 7-Eleven cups.

And that brings me to the review you wrote in 2008 of elBulli—where you had an elaborate, molecular-gastronomic meal. I would have expected you to deride it, but you took it as performance art.

Definitely. And I do think you can tell when somebody preparing your food is flying by the seat of their pants, that they’re trying new things. They’re taking the old and making it new. They’re making the new, the unexpected. They’re displacing the ideas of the old. I had to take that, my mouth told me to take what I was doing very seriously and with joy. I had no idea what I was eating. None. I left there starving after, what was it, 42 courses plus dessert. My wife and I ate for the next hour back in our hotel room. But that wasn’t what it was about. For me, it was about 100 other experiences—it just wasn’t about making your stomach feel American and full.

You live between Manhattan and Connecticut?

Well, I write better in Connecticut. I just do. Although the coffee is a little bit more of a problem because I have to drive 12 minutes to the service station, which has terrific coffee. And I’m a cow-whisperer. Which I was taught to do up there by people that maintain these heritage cows nearby. And that’s my only hobby now—it used to be opera. But that got too expensive.

So I found that this is nice, to kind of be with cows, and start to learn another language, to communicate. And it’s a very beautiful thing. You just move in a way that develops a language that they understand, and the way they move, you begin to understand. It’s pretty amazing except for big male bulls, who are just like all men: insane.

How much impact do you feel you have in your role as art critic?

I think that art critics are 100 per cent free. We can write and say anything we want with no fear. Although no one realises this. Why? Why can we do this? Because: no art critics get paid well. So you’re not going to lose any money. Critics are free, and do we have power? No. Can I make a career? Well I’ve tried to break careers and it hasn’t worked. So, I have to accept that. Nor can I make a career. As my wife has said, what we should work for is not power but credibility. A voice that people at least can believe. So when you read me, and you hate me, and think I’m an asshole, at the least I want you to do two things: believe that this is more or less the real me, as real as I can be in print, and the other thing is I hope you read me from top to bottom, and I don’t say that cynically. I can’t write if writing is without readers. I write for the reader. And that’s what I want. I’m not here to be loved by the art world. That would be nice, but that’s not what we write for. That’s not what this is about. Critics don’t have power but, man, they’re free—so free.

But too many critics, way too many critics, write either only positive or descriptive reviews. The weirdest are those that write in a kind of Mandarin- theoretical jargon that frankly no one understands. I have no idea what they’re saying. Nor does anybody! It’s written by 55 people for 55 other people like them.

“…older white men like me, I don’t want me to get another job. It kills me to say that. But, c’mon! It’s time to start hiring other people”.

And then they go to each other’s seminars and each other’s panels and drink the same artisanal coffee, and they get the good jobs! They get the ten-year positions, they get the healthcare, and the rest of us: we got the art world. We’re going to be just fine, art is doing just fine. Even with all this sort of craziness about money, art will be fine. Once the money goes away again, all of this will change again. It’s no problem, but older white men like me, I don’t want me to get another job. It kills me to say that. But, c’mon! It’s time to start hiring other people.

Those that you feel write in an overly academic jargon—do you think that’s an attempt to keep some kind of importance or power in a world of art criticism reduced to listicles and Instagram posts?

Very much. I think that’s a beautiful observation. I think it’s both commendable to not give in to writing listicles, or the ‘8 Best Works of Art at Frieze’, or the ‘15 Things That Sold at Art Basel’. But it’s also a defence mechanism. They also keep power. The writer is never vulnerable. They never have an opinion that isn’t pre-approved. They never like art that’s not already, kind of, government art-world inspected. And really, if you read them carefully, you have no idea what they think of the work. We’re all idiots at home, just doing the best we can.

As you’ve said, you’re kind of part of a dying breed. What’s the future of art criticism?

Right. I think we’re in the dawn of a new age of the critic, which thrills me. Just thrills me so much, that when people realise that we can all self-publish, since there is no money in this, that makes us free to do anything. Criticism is not going to die, only one delivery system for it will probably be curtailed. But art will be just fine—and so will criticism, it won’t die.

That’s an optimistic vision of the future…

But none of this acknowledges climate change!

Correction: it’s an optimistic vision of the future, if there is a future.

And I won’t be alive to see a billion people retreating from the coast. But even then criticism will eventually re-emerge, and so will art. Art has been with us since the beginning, and my guess is that it’s not done yet.

The Gourmand is an award winning, biannual food and culture journal. Each issue features 120 pages of specially commissioned words and images—The Gourmand’s content is creative, timeless and exclusive. The journal is printed on high quality papers by specialist art book printers. Founded in 2011 by David Lane and Marina Tweed, The Gourmand is published by Lane & Associates Ltd.