Paul Evans is the Managing Director of Fourth Estate Creative, a content creation company working across print, digital, web and video. Below he talks about their unique approach to employment – the Freelance Fellowship.

Full-time employment rates are falling sharply, with more and more people moving into freelance or contract positions. The number of self-employed people in the UK has jumped from 3.3 million in 2001 to 5 million today. This move towards the so-called ‘gig economy’ is a double-edged sword, driven by two very different trends.

The first is a move by businesses towards a commoditisation and distribution of work, facilitated in part by the peer-to-peer technology of the ‘sharing economy’. This move was spearheaded by companies like Airbnb and Uber, building on an approach used for years by platforms like eBay. Rather than the sale of products, this newer breed of companies facilitates the sale of the work or resources of others in precisely the quantity required, without the need to cover the cost of any overheads when those services are not being supplied.

This makes a lot of sense when the commodity being traded – like the unused spaces offered by Airbnb – might otherwise go to waste. Selling the unused capacity of productive labour can seem to follow the same lines, but as buyers become more reliant on these platforms, so too do the workers, who can find themselves effectively employed without any job security, minimum wage, pay reviews, sick pay, holiday pay or other benefits.

And once their services are commoditised in this way, workers can only compete on cost, leaving power in the hands of buyers and driving down rates. Depending on how they are run, freelance platforms can also have this effect; driving freelancers to offer more and more for less and less.

Creative work and content should not be treated as a commodity. The services offered by taxi drivers and couriers are perhaps interchangeable – where one driver is exactly as good as the next; this is at least arguable – but those offered by creative freelancers are certainly not. Aside from the impact on workers, this move is bad for content consumers – commoditisation requires work to be standardised, undifferentiated and therefore, by definition, unexceptional.

The second theme at play, offering a much more positive perspective, is the move towards flexible working practices. This represents individual workers breaking free from the restrictions of the nine-to-five, finding their own best ways to work – when, where and for how long it suits them. This can be enormously liberating for any worker, but for many – like stay-at-home parents and those with long-term physical or mental health conditions – it can be the only realistic alternative to not working at all. According to an IPSE report, the number of mothers working as freelancers doubled between 2008 and 2017, with them now making up 1 in 7 of all self-employed workers.

Freelance Fellowship

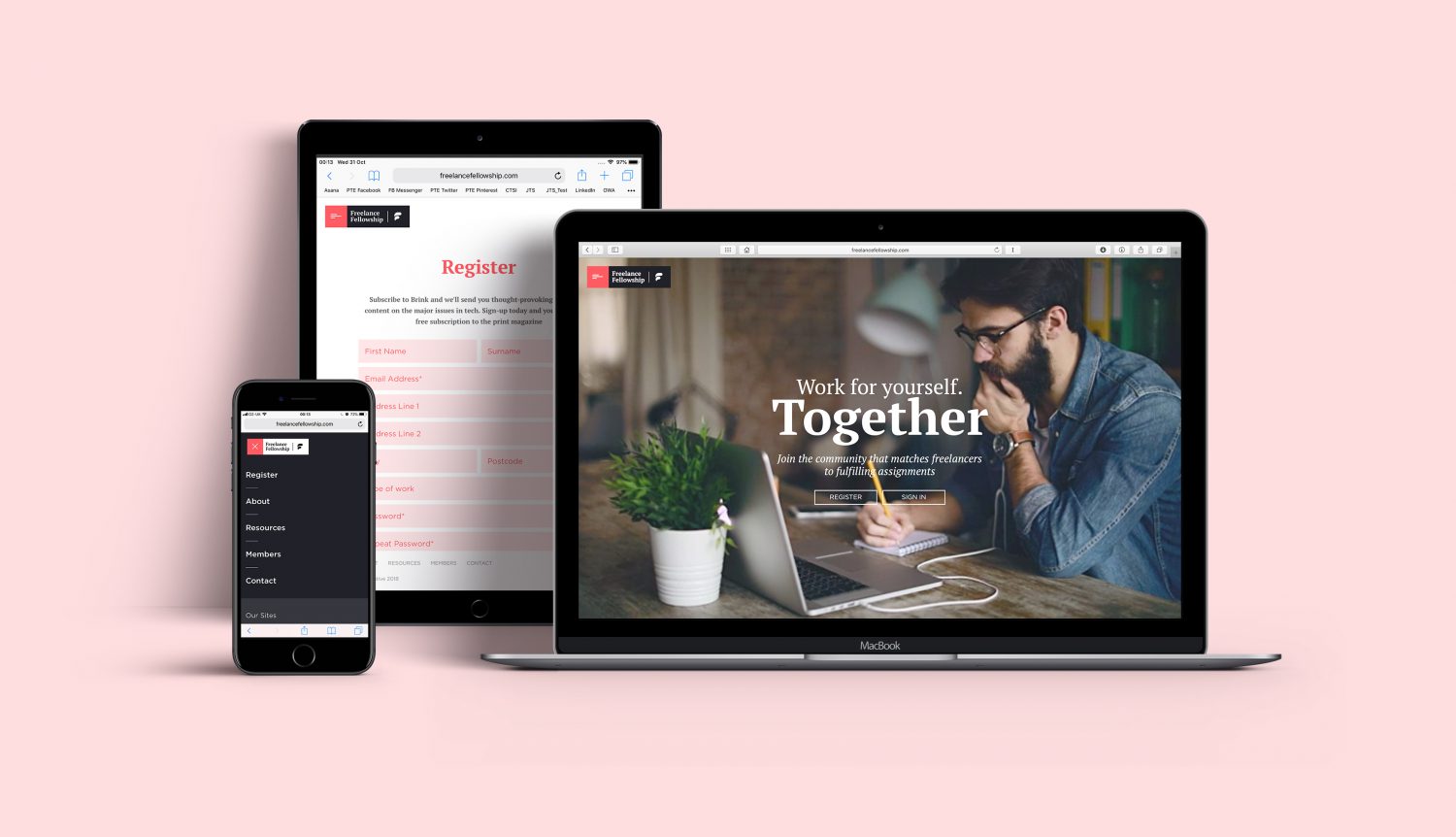

Last year, my agency set up the Freelance Fellowship platform, with the stated intention of connecting freelancers with fulfilling projects. Originally just a nickname for the band of freelancers I’ve worked with through many projects over the years, we decided to open the Freelance Fellowship up to anyone with the skills, knowledge and ability to help us do better work. Already the influx of new talent has helped us to take on many new projects we couldn’t have managed otherwise.

Before opening the platform to the public, we gave a lot of thought to the above two themes of exploitation and liberation and how we could help to support the latter without slipping into the former.

We believe if you want the benefits of freelance workers – low overheads, flexibility, specialism – you should provide benefits back to the worker – flexibility to work whenever and wherever they want, pay for work, not time, and always pay at the same rates (meaning they can compete on time, a proxy for competence, rather than on cost), help to find them relevant and fulfilling work, deal with difficult clients on their behalf and don’t micro-manage them. Perhaps most important of all, if you expect immediate availability, you should be prepared to pay immediately as well. We laid out this manifesto of sorts in our approach to freelancing.

The Freelance Fellowship currently only serves our own business – through it we have our own private army of skilled creatives that allow us to offer a huge range of services as a ‘virtual agency’ with only two staff, no premises and all work carried out remotely – and we have no current plans to change this. Of course, we work with clients who want access to the talent pool we have built, but these commissions go through us, meaning we can look after our freelancers and pay them standardised rates, immediately on completion, not when the client gets around to paying.

Creative Work

This does mean we don’t have huge scale – we don’t have a constant flow of freelance jobs waiting to be fulfilled. But this might be particularly necessary in the decidedly differentiated world of creative work. As highly influential computer scientist Jaron Lanier has put it: “Right now, if there’s nothing but a bunch of individuals and one giant tech platform there’s this bizarre situation where we’re petitioning the central authority… to police our own behaviour, and it’s just not tenable – we’re demanding authoritarianism.

“And the way round that is to create middle-sized organisations that are analogous to things like scientific journals or universities or trade unions where you can voluntarily join these things and they collectively bargain for you so you can get paid decently instead of having a giant race to the bottom. And they can become brands in themselves that enforce quality and become trustworthy and so we have to create this sense of intermediate structures.”

When small or medium sized collectives or organisations like ours work together with freelancers, the power is much more balanced. And this is particularly true in creative industries where freelance working really can be a net positive. The figures already show that in the creative industries, 35% of the workforce is freelance, compared to 15% of the economy as a whole, and some 95% of creative businesses are micro-businesses (defined as 0-9 employees). There are some particular challenges for creative businesses that make sense of these statistics.

Variety

A creative business needs to offer variety in its work. Of course, it can be important for a creative business like a publisher to establish a consistent style and approach to its work, but increasingly many creative businesses find themselves needing to produce work in many different styles and across many different platforms.

As a creative content agency, we certainly do. And it’s important to recognise that print design and web design are not the same thing, that journalism and copywriting are not the same thing, that animation and illustration are not the same thing. They take very different skills, knowledge and approaches. Companies that ignore such differences run the risk of producing bad work and of pissing off their creative staff.

Many creative companies can’t afford the overheads to employ one designer for print, another for web, another for graphics and another to produce marketing collateral – so the same person ends up doing it all. They probably don’t enjoy most of it, and they often won’t do a consistently good job. Variety is not just about keeping things fresh either. There is a real need for so-called ‘snipers’ – workers with a very specific set of skills. Whether it’s 3D modellers or Michael Caine impersonators (true story), creative companies will always need some people outside their core abilities.

Management

Managing creative people can be very difficult. In fact, managing people of any sort is difficult. From almost the beginning of my professional life, managing other people has been a big part of my work. Working in magazine publishing as a production manager, operations director and later as a managing director I’ve been in charge of many resources and there is much that needs to be learned to allow you to do a good job. I’ve had to learn about production, reprographics, IT, countless software programs, finance, budgeting – the list goes on – and I’ve always set myself the goal of trying to learn (at least to beginner level) the work of anyone I’m managing. Having overseen writers, subeditors, designers, developers and videographers as well as comms, marketing and sales teams, that’s been no easy feat. But learning the technical skills of these roles has always seemed easy compared with understanding the people doing them.

Grasping what motivates individuals is the most difficult challenge most of us face in our work. Companies often treat the management of human ‘resources’ as a ‘soft skill’ that – outside the HR department – requires no specialist training. Getting to grips with what makes people tick is not just a professional puzzle – it’s one of the fundamental challenges of our existence. It has been the driving force of countless philosophers, poets, authors, filmmakers, scientists and others for millennia. It’s no wonder there are so many bad managers.

Times are thankfully changing and many focus on the need to lead and to motivate rather than to micromanage, but the fundamental assumptions of the workplace – that you arrive at a specific time, work unabated for two four hour periods, do as you’re told, get ‘disciplined’ for not doing so and create the work the company needs, not the work you want – mostly still sit as a bedrock.

Pressure from inexperienced or unskilled managers to make subordinates productive at any cost leads to conflict. Yes, some people will take a break to read the news, go on Facebook, watch a YouTube video. Paying for people’s time, rather than work, makes it feel like this is money being stolen from the company. But creative work simply doesn’t come in uninterrupted 8-hour bursts and being ‘told off’ should not form part of any respectful adult relationship.

Often these bad managers were just good creatives who got promoted to overseeing more junior people with the same skillsets. This can be a seriously misguided approach. Understanding the work is much less than half the battle of good management and being good at something doesn’t automatically qualify you to manage other people doing the same work. Bad management costs a creative business enormously, because good creative work requires the proper motivation.

Motivation

Motivation is incredibly important in creative industries and the standard model of work could have been deliberately designed to stifle it. Most workplaces are designed around a production process. Work comes in and moves through the production workflow, with value added at each stage before being shipped to the customer.

There’s often no incentive to produce better work. Workers will rarely receive individual praise. They will likely have little say over the type of work they are given or over what the final product should look like. If they don’t work fast enough or become distracted a manager will step in to direct them back to their work.

This process might be good for manufacturing spoons, but it can be fatal for the creative process. The motivation to do the work is all applied extrinsically, with no reference to how the creator of the work is intrinsically motivated to act. Going freelance is often the only way creative people can try to design a job that involves doing things they already feel motivated to do.

More modern approaches to employee incentives like free food, social events, team-building and table tennis are often appreciated (if somewhat cynically), but rarely have a real impact on the employee’s connection to their work. Of course, freelancers sometimes have to take on jobs they don’t enjoy, but if you take the time to tailor the projects you commission to people’s individual skills and interests you will simply get a better product.

Practicality

A key factor in the movement towards freelance working in the creative industries is simply that it’s now practical to work this way. The ubiquity of broadband internet, the availability of cloud-based storage, creative software-as-a-service, online workflows, instant messaging and conference calling all contribute to making ‘virtual’ working a genuine alternative to office-based employment. Of course, the individual nature of most creative endeavours makes it work in this industry in a way it wouldn’t in others.

Our connected world also means that finding a skilled and professional freelancer these days is relatively easy – especially if you open your search to the whole world (and gig work is a huge driver in emerging economies). Compared with the financial and time costs of recruitment processes that look for workers in the small pool of candidates that live within commuting distance of the office and – regardless of skill-level – will ‘fit in’ with the rest of the team (really an irrelevant detail and one that works against the goal of diversity, both of background and personality) it can seem absurd to hire in.

Remote working requires more direct communication and has actually been shown to increase workers’ sense of connectedness to their teams, even if they’re thousands of miles away. Importantly for creative workers, it also allows you to communicate when you’re ready, rather than being forced to do so just as your creative juices are flowing or you’re deep in concentration.

Results

Creative workers who switch from an office to freelancing or remote working can often be astonished what they can achieve in a single day in the absence of endless impromptu meetings, unchosen music or loud and annoying colleagues. You can even take an hour or two to read the news relatively guilt-free – or at least less surreptitiously – and still achieve your daily work goals.

One in ten UK workers travel for 3 or more hours a day to get to and from their workplace. Leaving the commute behind gives freelance workers a far better work-life balance, with no cost to the companies working with them.

The notion of people ‘working from home’ as shirkers is very familiar to all of us. No doubt there are many real-world examples of people who don’t enjoy their work dropping productivity when they are not under the watchful eye of a middle manager. But good creative workers tend to enjoy, even love, what they do. Often, they’d still be doing it even if you weren’t paying them. I know many writers, designers – even web developers – who, after a hard day’s work, relax by doing more of the same, but on their own terms. All of the hardest working people I know work for themselves. Especially if they are being paid for their work not their time, companies need have no concerns about freelancers not pulling their weight.

Simply put, when people are properly motivated, trusted and respected they simply produce better work and on a more consistent basis.

The International Magazine Centre is delighted to be working with Fourth Estate Creative on our low-barrier-to-access training course for publishers. Find out more on our Training page.