Tom Hawkins heads up Work With Words and is a former journalist with more than 15 years’ experience working in B2B communications. His writing has been published in titles including The Independent, Huffington Post, City AM, Campaign and The Grocer. Here he discusses how data influences what we view online, and how good editors are now more important than ever.

A couple of years ago, I bought my first ‘proper’ bike. It was far from top-of-the-range but to me, with its nail-polish-red paintwork, it was something special. It looked like it was travelling at speed when it was standing still. I was smitten.

During the post-purchase honeymoon period, the bike took pride of place in the kitchen before a few subtle hints gave me reason to think this was not a situation with long-term potential.

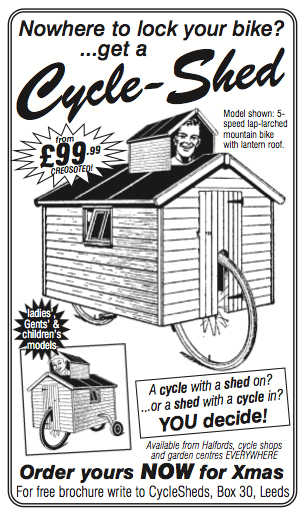

The time had finally come. I needed to buy a shed.

Not only would it provide shelter for the bike over the coming winter months, but it would also become home to my growing ‘collection’ of half-used paint tins and the gently rusting toolbox long since abandoned by the back door.

Defined by data

Dimensions and budget established, I turned to Google. Within a few hours, the deed had been done and within a few days (including one particularly sweary afternoon), the mission was complete. The corner of our garden now contained a compact wood-panelled temple to cycling and DIY. I had officially become a shed owner.

Only I forgot to tell Google.

On the internet, I very definitely remained a shed buyer. Right at that point, I had never less needed to buy a shed, and yet here I was being relentlessly chased around the internet by garden buildings of every shape and size imaginable. These ads had been deployed, like heat-seeking missiles, to hunt me down and convert the clear purchasing intent I had shown just days earlier.

I am not alone in this experience, I know. It may not be sheds but everyone has their own version of this ‘programmatic ads gone bad’ story.

From a pure data perspective, it makes absolute sense: IF user = looking for sheds, THEN show user shed-related ads. But it also highlights how data is rarely able to factor in the complex nuances of the buying process, or account for the tangled relationship between our online intentions and what actually happens in our (potentially quite mundane) real lives.

Pairing logic with reason

Even now, living in a data-driven digital age, human life is rarely linear. There’s still an awful lot of colour in those grey areas and a lot being said in the silences. Sure, we need to draw on data to guide us, but it needs to be carefully blended with insight, interpretation and analysis to create something truly of value.

Data, while incredibly potent, should be seen as raw ingredients, and they can be used to produce very different dishes depending on the creativity and skills of the chef in question.

And so it is with editors and writers. Data and analytics will let you know what an audience is reading, seeing or hearing, to what extent they are doing it, and where they might go next on their journey, but there is real skill in interpreting those clues, digging beneath the surface and understanding why.

Speaking to a rapt room of journalism students at City University several years ago, the brilliant Gill Hudson spoke of the importance of investing in your hunches. It is the skill of editors and journalists to ask questions of the information in front of them and to pull the answers apart before reassembling the pieces into a story using a mix of reason, judgement and creativity.

In search of more

But when things get tough and push comes to shove, do you back your hunch or back the data? Understandably, the concrete nature of hard numbers has strong appeal, but when there is little guidance from the hands of a good editor, it can have consequences.

There have been high-profile examples of big TV series that have taken themselves down paths of no return – or certainly into creative cul-de-sacs – where you can’t help but feel editorial integrity has been compromised to breaking point along the way.

It starts with a successful combination of ingredients that have been artfully prepared and delicately seasoned to perfection. But then there’s a need to make it ‘more’. So there’s more ingredients! More seasoning! More cooking! But, inevitably, it makes for less.

Game of Thrones found huge success with a formula that can be crudely distilled down to ‘CGI dragons and shocking violence’. And so we got more and more of those things. Only you start to become a bit numb to the violence. The shocks somehow become less shocking. The impact of the big dragon-y, dramatic set pieces become slightly diminished.

All the while, the characters into whom you’ve invested time and emotional energy become that bit fuzzier around the edges, and narrative arcs become truncated by unsatisfactory compromises. IMHO, the final few episodes of GoT (albeit a visually epic bit of TV) felt a bit like watching someone playing a video game called Dragon’s Destruction before a final denouement where we were made to sit through a meeting of the Westeros Regeneration Committee. (Maybe Stewart Lee was right.)

Forging deeper connections

Anyway, the point being that good editors and writers understand their audiences – it is their job to deliver what they want, and good data lays a lot of the groundwork. But it is also partly about exercising judgement and control, crafting an experience that engages the audience in a long-term relationship. It’s about shaping a narrative and presenting them with things they didn’t even know they wanted.

Today, given the detangling of content and platform, there is much wrangling over what constitutes a ‘magazine’. The word itself comes by way of French (magasin) and Italian (magazzino) via the original Arabic word makhazin, meaning storehouse, and the art of the editor is knowing what content to put on those shelves that will attract, delight and surprise not just readers but website users, listeners and all other people at the end of all other brand touch points.

It might be a printed magazine, it might be a data-driven B2B information service, it might be a podcast but at its heart there is a guiding voice of the brand – a real person who speaks to the audience as individuals.

Ultimately, it’s an editor’s responsibility not to create content but to build trust, and to use that as a platform to forge valuable connections with audiences, whether at scale or within a tightly defined niche. Perhaps more than anything else, it’s the depth of those connections that defines what makes a ‘magazine’ today – something highlighted so well by the Pay Attention! research carried out by Magnetic.

Finding the balance

All of this is not to say that data should be ignored. Far from it, particularly at a time when social listening and web analytics paint audience behaviour in such immediate and vivid colour, and when machine learning has the potential to create patterns out of seemingly shapeless masses of big data.

Even for the content creation process, the potential for artificial intelligence can’t be ignored, particularly in the context of certain markets and applications. For example, AI journalism tools are already widely being used in structured financial reporting environments to deliver facts and figures at speed, and at the PPA Festival this year, Press Association Editor-in-Chief Pete Clifton spoke of how its RADAR automated content service forms a growing part of news reporting among local and regional publishers.

As he underlined, however, the technology and the data on which it feeds are complementary to the skilled work and editorial judgement of the journalists and editors involved. Such developments don’t change the need to listen to your hunches, back your big ideas and have the courage of your convictions. After all, if you rely too heavily on the data, you might just find yourself trying to sell sheds to a whole load of shed owners.