Should an economic relationship with nature be one of a unilateral character, with humans receiving from nature, or a bilateral one, where nature also receives from humans? And what extreme scenarios could emerge with the commodification of nature? Nicolas Canon wrote this article for It’s Freezing In LA! for their June 2019 issue.

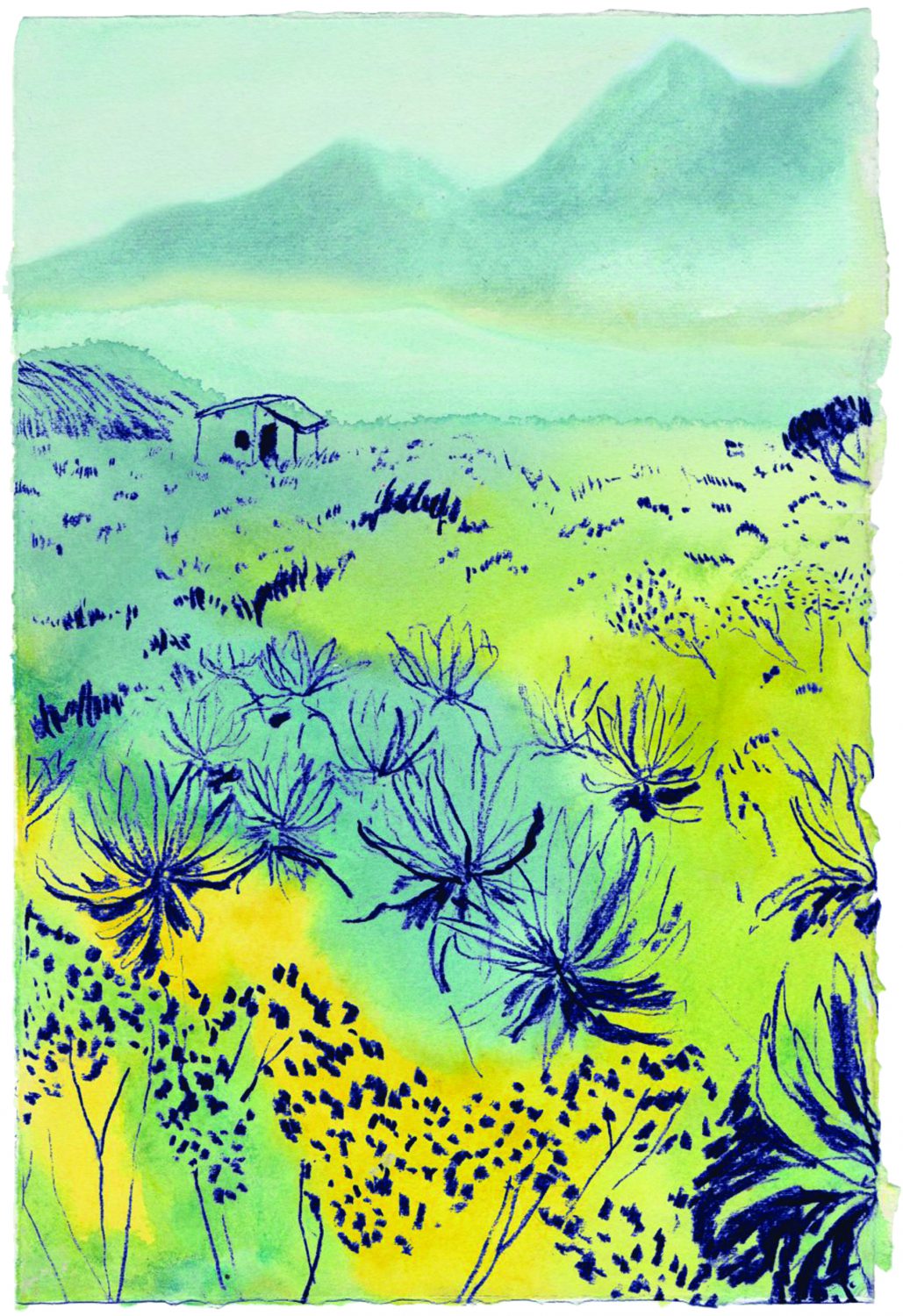

In 1945 Aurelio Arturo, a Colombian poet and lawyer, described his country as a place ‘where green is of all colours’. Picture a tropical country with ecosystems ranging from the Pacific to the Caribbean coast, and from glaciers, 5,000 metres above sea level, to the Amazon Rainforest, and you begin to understand Aurelio’s statement. Green, in this corner of the world, is a much more complex colour.

High in the Andean Mountains there is an ecosystem with a rare kind of green, low vegetation and a mysterious mist. This place is called the Paramo and it is located in different regions of Colombia, between the tree line and the perpetual glaciers. In Pre-Columbian times, before the Spanish arrival to the central high plateau in 1537, the Paramo was considered by the Muisca Indigenous civilization as a territory that held the forces of creation and the origins of mankind. The Muisca statement has proved true.

In 1819, hundreds of years after the downfall of Muisca civilization, Simon Bolivar and his liberating army crossed the Paramo de Pisba to fight for independence from Spain. Many soldiers died in that crossing due to the extreme low temperatures of the Paramo, but the surviving soldiers fought, allowing Colombia to gain independence. For many years after the Spanish Conquest, and after independence, this mystical ecosystem was considered a cold and wet territory, with no real relevance to the national economy. It is only in the last decades that we are starting to understand that the Paramo is a true sustainer of life, as the Muiscas thought, and that it is also the sustainer of our economy.

This ecosystem has been called the ‘water factory’ of Colombia, since it produces most of Central Colombia’s freshwater of central Colombia.

The 35 million people that live in the Andean Region of Colombia benefit directly from the service that the Paramo generates. These benefits include household water consumption, industrial activities, crop production, generation of energy through hydroelectric dams, and recreational and cultural services. These benefits are known as ‘Ecosystem Services’, referring to the benefits (goods and services) that ecosystems provide to humans. This concept seeks to reveal the social features of ecosystems, apart from the mere biological features.

Having in mind the number of benefits that the Paramo creates, we must determine whether and how we should remunerate nature’s services. Should the Paramo have its own patrimony? Or must there be an economic retribution to the people that inhabit the Paramo? We must ask ourselves whether an economic relationship with nature should be one of a unilateral character (humans receiving from nature), or a bilateral one (humans receiving from nature and nature receiving from humans).

The idea that ‘conditioned and voluntary transactions’ should be given by beneficiaries of ecosystem services to those responsible for preserving the Ecosystem has been implemented not only in Colombia, but also worldwide*.

This regulation strategy, based on the creation of incentives for environmental protection has had massive environmental achievements in Latin America. This is particularly the case in Costa Rica, which went from having a percentage of forest cover of 21% in 1987 to 52.4% in 2013.

The success of such a strategy in certain countries of Latin America may be explained by the region’s characteristics. The rate of poverty in rural areas creates dependency on the exploitation of land as a sole source of income. Also, due to the abundance of natural resources found in Latin America, there is an urgent need to regulate their extraction. Finally, Latin American states often lack the administrative capacities to implement traditional command and control regulatory strategies, creating a need to develop alternative mechanisms.

In Colombia, actors that were previously contributing to environmental degradation are now a key part of the solution.

Some parts of the Paramo are inhabited by local farmers, who often exploited the land to grow potato or raise cattle so as to earn a modest income for their families. Without knowing it, these farmers were causing severe ecological and economic damage since the destruction of the vital ecosystem would have an enormous impact on the production of water. Instead of denying the farmer an income with a policy that completely bans the use of his land, they will instead be paid to carry out an activity (protecting the Paramo) that they wouldn’t have done otherwise, and that has a massive collective benefit.

Payments for Ecosystem Services have been implemented throughout Colombia, far beyond the Paramo. Payments are made for services including water, CO2 absorption, and increasing biodiversity. In some cases the payments are made by large companies like the BanCO2 scheme; in others by the government, like the PES Program of the Department of Cundinamarca. The farmers are then obliged to refrain from exploiting the areas of their land that produce the most environmental benefits. This means that some lands are left unexploited, others are partially exploited.

The success of Payments for Ecosystem Services depends on the environmental values of the community where it is applied. For example, among Indigenous Peoples such programmes may be useless, since a payment for conservation may be against their cultural norms, as nature is of intrinsic value to these communities.

The main problem with the general idea of putting a price on nature is defining the limits. What would happen if the Paramo were entirely owned by a foreign multinational? Could a river be owned by a private actor? Can a whole species of animal – say, the world’s population of polar bears – be owned by Coca Cola? Will we have to pay for the oxygen we consume daily? These questions may sound absurd but they emerge when we imagine an extreme scenario of the commodification of nature.

The idea of a society that only respects nature when being paid might be uncomfortable to many. Putting a price on nature may overshadow its intrinsic value and may strengthen the view of nature as a passive and exploitable resource.

Payment for Ecosystem Services is an environmental governance tool worth studying as a realistic approach to our current economic system with the capacity of reconciling interests in a commodified world. However, the success of such a program will depend on the region’s social and economic structures. Colombia’s relationship with the Paramo serves as an example for understanding how humanity constantly shifts its relationship with nature.

From the sacred ecosystem of ancient civilizations, to the underestimated humid land, to the valuable ‘water factory’, the Paramo has unconditionally blessed us with its generosity. How and why we value nature will define the way in which we protect it and will shape society’s environmental values. Those environmental values will shape the policies of tomorrow.

* Conditioned and voluntary transactions can be understood as agreements without coercion be- tween buyers and sellers, subject to mutually accepted conditions.

It’s Freezing In LA! is an independent magazine with a fresh perspective on climate change. It acts as a platform for nuanced, complex and insightful discussions on climate change and environmental issues, drawn together with bold illustrations and beautiful design.

Since inception, the magazine has drawn writers and illustrators from all over the world. Featuring topics that stretch from guerrilla gardening to rain dances, and theatre lighting to universal basic income, the magazine untangles the diverse intricacies of our relationship with the environment. Illustrators explore the algal blooms filling seas and the shades of green in the Colombian Paramo, poets consider childhood in the face of climate catastrophe, and interviews with pioneers of the green movement reflect on its future.

Shortlisted for Stack’s ‘Launch of the Year 2018’, and listed as one of The Guardian’s top zines about sustainability in 2019, this is a magazine which pulls the green movement into modern, bright conversations about our future.

Find out more and subscribe through the It’s Freezing In LA! website.