First published in October 2018 by Intern magazine, a platform for and by the creative youth, empowering the next generation through content, support and training.

Jaheed Hussain has never been taught by a tutor, visiting lecturer or industry professional of colour in his time at university so far. Now he’s pushing for change.

As a current student, I look to creative education and industry to set an example when it comes to diversity. Their actions are hugely influential in how students like me perceive what’s going on around them, and from my perspective, there is much work to be done.

When I attend design events, keen to get involved in broader conversations around my discipline, I rarely see any other people of colour. For me and so many other students of colour, the realisation that we are so underrepresented makes us feel like we don’t belong.

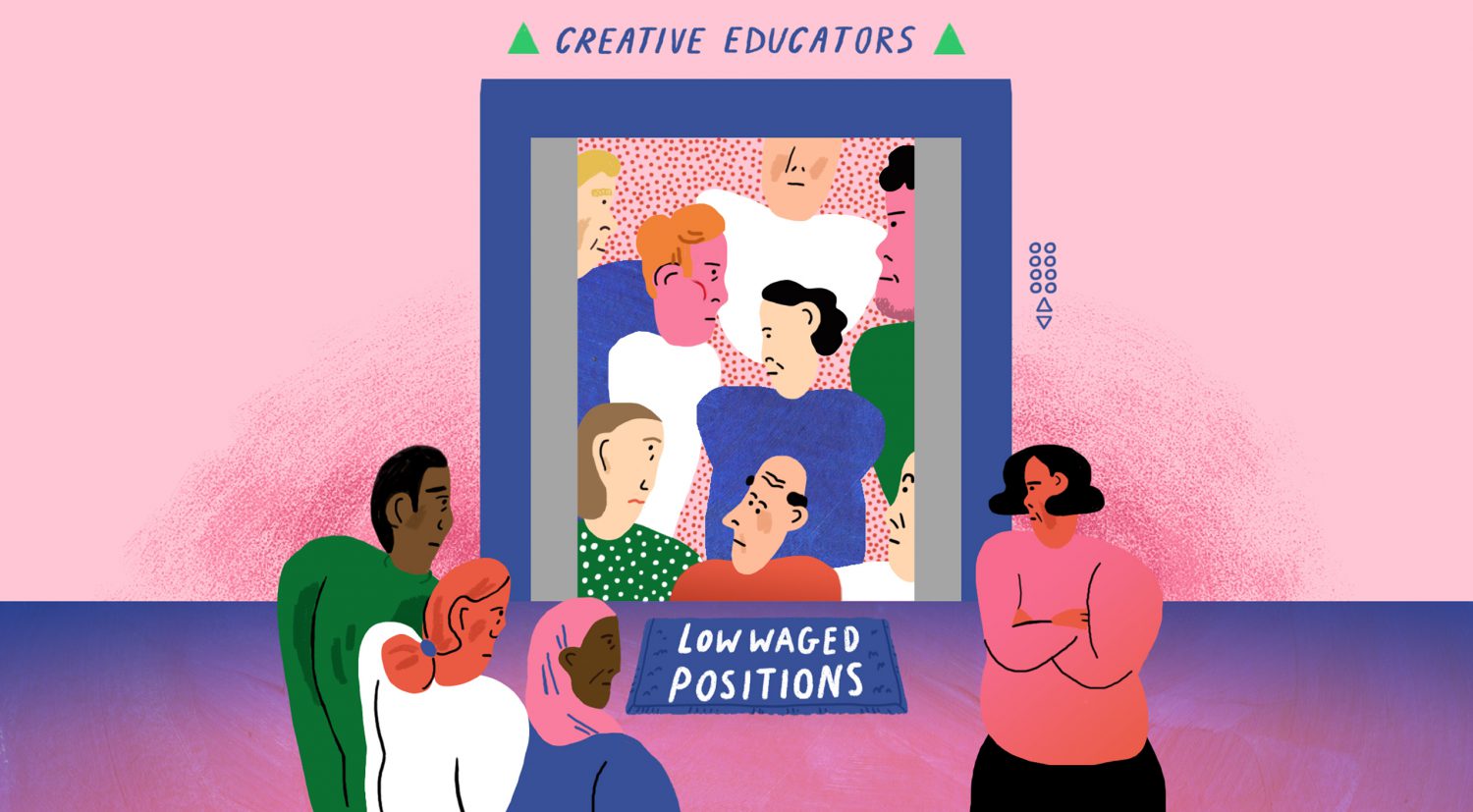

In creative education, the Higher Education Statistics Authority (HESA) records that between 2016 and 2017, only 13.8% of the 206,870 staff in academic posts are from backgrounds that aren’t white. More importantly, those who do have jobs in academia are rarely in senior positions, with recent figures showing no black staff in senior roles across the UK. It’s no wonder that Reni Eddo-Lodge, in her book ‘Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race’, reveals that “70 per cent of the professors teaching in British universities are white men.” As Reni puts it, this is “a dire indication of what universities think intelligence looks like.”

“Simply ‘making the grade’ isn’t enough”

In industry, the picture is no different. Research by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) discovered that, in 2015, the creative industry had only 11.4% of workers from an ethnic background. Similar to creative education, they are also rarely in senior positions. For example, some of Britain’s foremost design institutions have much work to do, with Fitch employing only white staff in senior leadership positions and Pentagram having only 3 out of 21 partners from a minority background.

Arguably, Pentagram and other companies and universities could contend that they are broadly representative of the UK non-white population as a whole (13%, according to 2011 census data). But, ask yourself, is that a genuine attempt at representation? Simply ‘making the grade’ isn’t enough. If all cultural perspectives are equally important, then these institutions must support those with diverse opinions, perspectives and experiences in a way that goes beyond just reflecting population statistics.

This state of affairs is pushing many organisations to advocate for better minority ethnic representation. “Diversity is one of the most important issues of our age”, argue the Arts Council. “Diversity and equality are crucial to the arts because they sustain, refresh, replenish and release the true potential of…artistic talent, regardless of people’s background,” highlight the Creative Industries Federation (CIF). And as AIGA have consistently emphasised, a higher proportion of diversity leads to more innovation, whether it’s in the boardroom or the classroom. So if the argument is accepted by these organisations, what’s stopping it from translating into education and industry? If we genuinely want to create change in terms of racial inequality and challenge cultural hegemony, we need to aim for far higher than just 13% of staff, particularly in senior positions. This greater visibility can also encourage creatives of colour to feel like they belong or to get involved in teaching, in turn helping to break the cycle of underrepresentation.

“As I enter my third year, there’s been no teaching, visiting lecture or industry talk by a creative of colour”

On my graphic design course, there is only a small handful of Black and South-Asian students inside a student body of around 260 across all levels. These low numbers can be traced back to the de-prioritisation of the arts in secondary education, where funding cuts led to a “28% drop in arts GCSE entries from 2010 to 2017” according to the Cultural Learning Alliance (CLA). Crucially, this lower uptake has a distributional element: as Sam Cairns, co-director at the CLA, has explained, students from more affluent backgrounds are more likely to be able to study the arts while those from poorer backgrounds (a category in which BAME students are overrepresented) are disadvantaged, unable to benefit.

Adding to that, as I enter my third year, there’s been no teaching, visiting lecture or industry talk by a creative of colour. Some of my peers and I feel disconnected because of this, but this also relates to every student, not just BAME ones, as they too are unable to benefit from the tremendous creative potential that different perspectives, experiences and cultural backgrounds offer.

A great illustration of the whitewashing of the arts can be found in the Creative Bloq article “25 names every graphic designer should know”, which, incredibly, didn’t include a single person of colour. It’s true that everyone on the list does have a high reputation, but are we really saying that there are no Black, East-Asian, South-Asian, Indigenous designers worthy enough to be mentioned? The author isn’t necessarily to blame personally, but the article shows the industry’s uncomfortable relationship with diversity. That it’s the first result when you search for ‘BAME graphic designers’ on Google only stresses this point. Only people within the industry, like the author, can re-frame that.

Similarly, after the launch of Google’s Art Selfie app, which matched users to art from around the world, it was found consistently to be matching people of colour to stereotypical and troubling depictions of their ancestry, such as slavery, with no acknowledgement of any other representation. Google argued that this was down to the Eurocentric nature of art history, but whether you accept that defence or not it’s nevertheless a serious indictment of the fact that, for a long time, art galleries often showcased paintings of white faces, or only problematic depictions of non-white ones, with little room for anything else.

Nowadays there are small signs of progress, with some galleries making moves to show more work by creatives from other countries and backgrounds, such as Tate Modern’s ‘Soul of a Nation’, Whitworth Art Gallery’s ‘Beyond Borders‘ and Nottingham Contemporary’s ‘The Place Is Here’ to name a few. But at present these exhibitions are the exception rather than the rule, with far more work to be done.

Change is needed, so this piece is a call for all of us, the industry of tomorrow, to create that change. Already we see artists and creators doing things for themselves, pushing for greater visibility. Gal-dem’s recent takeover of the Guardian Weekend supplement helped to broaden perspectives, while Stormzy has announced two full scholarships for Black students at the University of Cambridge to counteract the institution’s famously white makeup.

Smaller initiatives can be just as powerful, too. Fresh Magazine, an innovative publication created by four graphic design graduates from Manchester School of Art, uses design to reveal attitudes about ethnic diversity. Fresh interview and showcase creatives while questioning the obstacles getting in the way of progress. “We were tired of the massive lack of ethnic diversity within our university … Students need artists to emulate,” explains co-founder Katie Jones. “If they don’t see designers of colour thriving, they’ll convince themselves they don’t belong!”

“A lecture, talk or workshop presented by someone from an ethnic minority background should be conventional, not exceptional”

Collectively, the Fresh team grew increasingly frustrated with the lack of diversity presented throughout their course, so created the magazine as a riposte. “I think designers of colour are starting to carve out their own paths. We all see the problem, and I think it’s movements like ours that are the only way to answer it,” says Katie. “If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem. With the support of everyone, including our white counterparts, we’ll deal with this problem a lot more quickly than if we stand alone.”

Due to the limitless nature of creativity, creative departments seem to be best placed to break the glass ceiling within the industry. One university with strong diversity and inclusion policies is Ravensbourne, however, they revealed that while 23% of their staff are from non-white backgrounds, only 9% of them work on creative subjects, demonstrating the big gap between policy wording and institutional reform.

I want to see creative universities hiring more teaching staff from non-white backgrounds, or at the very least, inviting creatives of colour as visiting professionals. Something as small as a lecture, talk or workshop presented by someone from an ethnic minority background should be conventional, not exceptional. This approach would create a path for junior academics to gain the experience required for more senior positions, thereby ensuring that “it’s a meritocracy” can’t be used as a defence for poor representation.

“Ask yourself, am I doing enough?”

To editors and writers, rather than a piece listing 25, all white famous names, I encourage you to use your platforms to uncover designers and artists that people should know but don’t. Dines, Shaz Madani, Manjit Thapp, Manshen Lo and Saffa Khan all spring to mind. Their work impacts millions and often references the underrepresented lived experience, giving voice to those who remain largely overlooked.

To colleges and universities, you need to talk more about the issue. Introduce tutors, lecturers and visitors that are from different backgrounds in creative subjects. Diversity spurs creativity, persuades students to learn from different perspectives, builds empathy and immerses them in new experiences, but the inescapable reality is that there’s a very small chance of a student being taught by someone who isn’t white. As such, all students can fail to benefit from questioning artistic hegemony and understanding the social and cultural dimensions to their art.

To the industry, whether you’re senior management or a junior designer, there are dedicated resources established to help you promote diverse talent. Organisations like Arts Emergency collaborate with creatives and help mentor young, underprivileged students in the creative field. The Arts Council, CLA and Creative Industries Federation regularly promote discussion of the racial and cultural dimensions of creative education and industry; follow their lead so that the issue isn’t just an afterthought. Ask yourself, am I doing enough?

To students of colour, as the industry of tomorrow, we can also help to make it happen ourselves. Podcasts like About Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge speak volumes about anti-racist activism and historical references by talking to activists, educating others about these topics. Let’s start new projects, write about these issues and challenge ourselves to learn from diverse sources, just like Gal-Dem, Fresh or any one of the thousands of POC creators with important things to say.

Education, industry and media often feed off one another, so let’s set an example that’s subversive yet inclusive, to the benefit of all.

Intern is a platform for and by the creative youth, empowering the next generation through content, support and training.

Visit their website https://intern-mag.com/ and follow them on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

The Crit is an independently produced series by intern starting important conversations about creative education. We’re looking to instigate dialogue that can open up clearer lines of communication between students, educators, institutions, graduates and industry because we passionately believe in the value of creativity.

Find out more about Jaheed Hussain’s work on his website and Instagram.

Find more of Sumeena Owen’s illustrations on Instagram.